Association remains strategically focused on providing solutions for specialties

With a mission “to promote the highest scientific and business standards in relation to the industry; and generally to take such collective action as may be proper for the establishment and perpetuation of the organic chemical independence of the United States of America,” the Society of Chemical Manufacturers & Affiliates (SOCMA) has endured from its humble beginnings and continues, after 100 years, to provide a forum for advocacy, operational excellence and commercial growth, while rooted in the principle of safe operations.

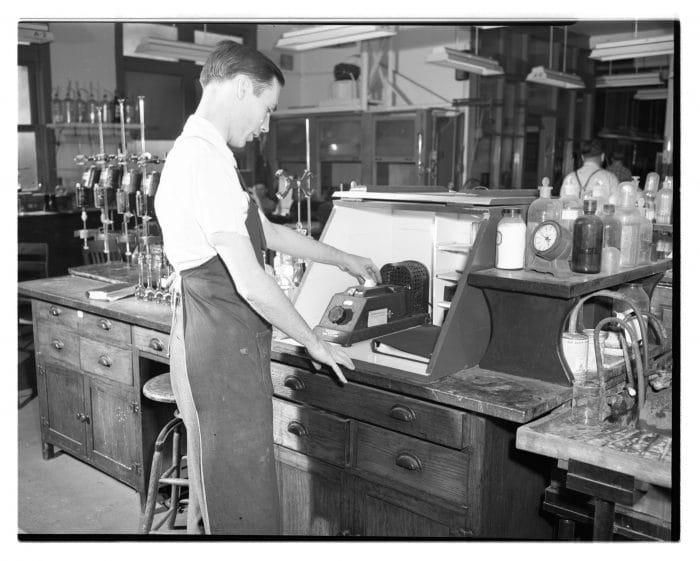

The Roaring Twenties were still just a murmur in 1921, when the Synthetic Organic Chemical Manufacturers Association was formed. The global economy was still recovering from the First World War, and much of what is today fundamental chemistry had yet to be developed. In that same year, for example, Friedrich Bergius first hydrogenated coal to oil. J. N. Bronsted only postulated his theory of acids and bases in 1923.

Herbert Hoover, Secretary of Commerce, addressed a meeting of manufacturers of synthetic organic chemicals, including dyestuffs, intermediates, pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals held at the Hotel Washington in the District of Columbia, October 28, 1921, at which the original SOCMA was formed. Hoover stressed the necessity of the formation of trade associations, especially from the standpoint of the Department of Commerce.

“Gentlemen, I feel it a great honor to be present at the baptism of this new trade association. The Department of Commerce has endeavored to establish a definite relationship with the great multitude of trade associations throughout the country. I have felt that the trade association is not only a great power for promotion of commerce but that it has a tremendous influence for good in the industry.”

Hoover noted a surge in the formation of trade associations and suggested it was “something that is vital, and something that is permanent in the economic system.” A century later, SOCMA has indeed stood the test of time, though it was by no means certain to last at the time of founding. If anything, the initial 36 companies were seeking a proof of concept. In his address, Hoover validated the importance of trade associations in keeping an industry going.

In the early decades of the 20th Century, the United States was largely dependent on Europe, particularly Germany, for dyestuffs and other specialty chemicals. The war effort put into motion a broad effort for industrial mobilization as well as tariff protections.

Hence, the closing terms of the SOCMA constitution stated the objects of the organization: “…to promote the highest scientific and business standards in relation to the industry; and generally, to take such collective action as may be proper for the establishment and perpetuation of the organic chemical independence of the United States of America.”

The vision of “chemical independence” seems to foreshadow the political isolationism that was ascendant in the following two decades. The same concept was echoed in calls for “energy independence,” arising from the oil crises of the 1970s and continuing through the shale bonanza of the 2010s. The irony is that oil markets have, from the start, been global, and specialty chemicals even more so.

Europe did not lie in ashes as it did at the end of the Second World War, but European nations were devastated socially, economically and politically.

The fighting in World War I had been over for about two years when SOCMA was founded, but the fighting over the peace had consumed most of that time. The second and final vote in the Senate, by which the U.S. refused to join the League of Nations, took place on March 19, 1920. President Woodrow Wilson never recovered from that defeat, or from the stroke he had suffered six months earlier.

Wilson was succeeded by Warren G. Harding, under whom Hoover served, then by Calvin Coolidge, and then by Hoover himself. The Progressive Era is widely considered to have started at the Turn of the Century with trustbuster and environmentalist in chief Theodore Roosevelt and lasted through the 1920s. But from Wilson, a Democrat, and accelerating through the three succeeding Republicans, federal policy was steadily less reform and more laissez faire.

Hoover was frank when he spoke about how he saw the relationship between government, and in particular with the Department of Commerce in particular, vis-à-vis industry groups. “The various trade associations present for the department a point of contact with business such as did not exist ten years ago. And by setting up a friendly relationship between the department and these associations, the department and the government are able to learn and serve the rightful aims, objectives, and needs of the different branches of the industry.”

However, Hoover was not just a cheerleader. He noted that the trade associations already functioning were, quite literally, in beneficial operation. “…they were engaged in a great range of educational subjects, matters of improvement in industrial methods, improvement of trade practices, interest in matters of transportation, elimination of waste, standardization of specifications, arbitration of trade disputes, and foreign trade.”

It is notable how many of those points are today elements of SOCMA’s strategic pillars and ChemStewards program, notably the principle “continuously strive to use resources efficiently and minimize waste.”

What today is considered a holistic specialty chemicals industry has converged from many different segments, with commonalities founded in chemistry and commercial production.

Thus, Hoover was not wrong when he remarked that the formation of SOCMA marked the nascence of a distinct type of business. “I particularly welcome the creation of this association because it represents a new industry….an industry that thrives by the use and application of the wastes of other industries. This turning to account what would otherwise be almost wholly waste products—mostly those that escape into the atmosphere or into the streams of this country.”

Given current understanding of the devastating effects of pollution historically, it might seem that Hoover could be one of the early champions of stewardship and sustainability. But Hoover, an engineer by training and an industrialist by faith, called on the industry to be creative and find alternative methods to repurpose waste streams.

“By these processes we add to the total sum of the commodities that we have to divide among our people. I do not think that it would be at all an overestimate to say that the wastes from wood, coal, and other products upon which this industry is based, have an annual value of upwards of a billion dollars if they could be turned to account…There is still an enormous field of waste to be overcome, of added value to be taken into the resources of our country. Today every coke oven that is not recovering its by-products is turning a loss into the air that can never be recovered.”

While Hoover captured the essential role of the chemical industry in the country’s economic development, and the role of the association in the industry, he could not have known that his exhortation to recover coke-oven by-products was clairvoyant. A shortage of anthracene, which is derived from coal tar, developed and was swiftly alleviated in 1922 with the synthesis of anthracene from benzene and phthalic anhydride.

The same year that SOCMA was formed, Congress passed the Dye & Chemical Control Act. It was an expansion of the 1919 protective tariff known as the Longworth Bill.

“The 1920s saw several technical innovations, mainly in the areas of increased color fastness and dyestuffs for synthetic fibers,” wrote Peter J.T. Morris and Anthony S. Travis in their “History of the International Dyestuff Industry,” (American Dyestuff Reporter, Vol. 81, No. 11, November 1992).

Notably, “chemists at Scottish Dyes discovered the first bright green vat dye, called Caledon Jade Green, which was popular for the next fifty years. With the introduction of cellulose acetate on a large scale immediately after the war, dye chemists had to adopt completely new approaches. Cellulose acetate called Celanese in Britain and Lustron in the United States; the term rayon was introduced in 1924.

“To that point,” Morris and Travis continued, “dyeing had been carried out in aqueous media [to color] fibers from natural materials. Ionic groupings polarized the dye molecules and that favored solubility. However, these groupings resisted attachment to cellulose acetate, which did not absorb water.”

The timing of the formation of SOCMA to guide and serve the U.S. industry was propitious. Just three years later, in 1925, two major European developments rearranged the global specialty chemicals industry. In the U.K. Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was created through the merger of the four largest British chemical companies.

On the Continent “the massive chemical corporation IG Farben was set up in Germany at the end of 1925” wrote Morris and Travis. “There were 67,000 workers, including 1,000 chemists. About 36 percent of sales were represented by dyes. Bayer’s Uerdingen factory specialized in intermediates, and Leverkusen, also in the Bayer sector, in azo dyes.”

1925 was also a seminal year at the lab bench, particularly in Germany. Carl Bosch invented the process for industrial production of hydrogen. The same year, Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch first made synthetic petroleum.

“The creation of IG Farben heralded and forced many changes elsewhere,” Morris and Travis noted. “Although ICI was similar in size to DuPont, and both had the largest ranges in their respective countries, they were no match for the giant IG Farben.

“Cartel arrangements were initiated by the two largest exporting nations, Germany and Switzerland,” they explained. “These were favored by new and existing national corporations and partnerships. The Germans, Swiss and French linked in 1928, and in 1932 they were joined by ICI. Much of the remainder of the worldwide dye industry before the Second World War was controlled, directly or otherwise, by the cartel, sometimes because of Swiss, French, British or German holdings.”

As an inherently international industry, the regulatory attention in specialty chemicals naturally gravitates to tariffs and trade. But for a national trade association, there always has to be vigilance on issues of competition.

According to the Federal Trade Commission’s official history, Congress passed the first antitrust law, the Sherman Act, in 1890 as a “comprehensive charter of economic liberty aimed at preserving free and unfettered competition as the rule of trade.” In 1914, Congress passed two additional antitrust laws: the Federal Trade Commission Act, which created the FTC, and the Clayton Act. With some revisions, these are the three core federal antitrust laws still in effect today.

The Sherman Act outlaws “every contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade,” and any “monopolization, attempted monopolization, or conspiracy or combination to monopolize.” That said, the Supreme Court has determined that the Sherman Act does not prohibit every restraint of trade, only those that are unreasonable.

As amended by the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, the Clayton Act also bans certain discriminatory prices, services, and allowances in dealings between merchants. The Clayton Act was amended again in 1976 by the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act, to require companies planning large mergers or acquisitions to notify the government of their plans in advance. The Clayton Act also authorizes private parties to sue for triple damages when they have been harmed by conduct that violates either the Sherman or Clayton Act, and to obtain a court order prohibiting the anticompetitive practice in the future.

In retrospect, it is remarkable that after a century, SOCMA is still performing its mission as expressed in its founding documents. Formed in the tumult after a world war, the association survived the Great Depression and another world war. It has advanced the science of chemistry and the ethic of stewardship. It has fostered both innovation and collaboration.

The founders would marvel at the instrumentation and manufacturing standards of today, and beam with pride at how the association they organized in 1921 continues to cultivate industry growth and profoundly impact the quality of life for all mankind.

Gregory DL Morris has covered the chemical industry for more than 20 years and has a vast knowledge of its history. Gregory has covered SOCMA with industry trade press for many years and authored this historic piece on behalf of SOCMA’s 100th anniversary.

Categorized in: Uncategorized