1920s

The specialty chemicals industry experienced remarkable development within the first decade of its formation in the United States. Throughout the 1920s, the nation became almost fully independent of foreign sources of supply for most of the critical products necessary for proper and economic functioning of industries, including the specialty chemical industry. Prices remained low, and in some cases, lower than pre-World War I. SOCMA membership saw tremendous opportunity still for the growth of synthetic organic chemistries.

They were confident in and eager to increase the impor- tance of the industry in the life and well-being of American citizens. By 1930, SOCMA was staunch in its duty to fully cooperate to keep the synthetic organic chemical industry an asset to the nation.

Key Decade Events:

- Dyes and dyestuffs were the key materials made by U.S. manufacturers who were working to stay ahead of foreign competitors.

- SOCMA member DuPont began “researching initiatives to manufacture dyes that [prior to WW1, Germans had supplied].” These initiatives kicked off innovation that spurred tremendous industry growth.

- By 1920, the U.S. had many synthetic organic chemical companies and formed an association for self- preservation. “…America has decided to have an organic chemical industry of her own, so that her children – (applause) – and her children’s children shall be safe.” – Herbert Hoover, address to the SOCMA membership at its first annual meeting, 1921

- October 28, 1921 – First Annual Meeting held at Hotel Washington, Washington, DC. Secretaryof Commerce Herbert Hoover’s address: “…a trade association is not only an enormous power in commerce, but has a tremendous power for good in industry, and it represents a new step in the whole social and economic development of business life.”

- 1921: Subcommittee on Poison Gas – Subcommittee on Poison Gas – Organic chemical industry used numerous potential warfare gases in time of peace, thus formed a committee to look into subjects of chemical warfare.

- 1922: Tariff Act of 1922 granted special protections to the industry, in the form of a new method of evaluating competitive imports for duty purposes.

- 1923: SOCMA worked with the U.S. Treasury and Commerce Departments on customs regulations and Tariff Commission, enabling “the most valuable aid to the development of this industry.”

- 1924: There was development of certain organic chemicals for civic defense. Police, banks, jewelers and others were protecting themselves, and American citizens, by use of tear gas. “When it comes to police and private protection, the use of gases for defense is growing stronger and stronger.””

- Early 1920s – The U.S. Tariff Commission began a monthly census of dyes and other synthetic organic chemicals; statistics that SOCMA members utilized for the benefit of their own operations.

- According to first Constitution of SOCMA:

- SOCMA comprised of “The Association of Dyestuff, Pharmaceutical, Intermediate and Fine Organic Chemical Manufacturers in the U.S. of A.”

- SOCMA’s formation “is the result of the unusual conditions existing throughout the world in the field of organic chemical manufacture, and the recognition of the necessity of co-operation between American producers of all organic chemicals in order to insure the permanent establishment of a complete organic chemical industry in the United States.”

- 1925: SOCMA formed the Patent Committee to examine all patents of interest to member companies in their sectors of industry to expand opportunities.

- 1925: Synthetic Methanol – President Herty made pointed efforts to keep this on SOCMA’s radar. Methyl alcohol was used in large quantities by the industry. In the early 1920s, a dispute raged as to the importation of synthetic methanol. The U.S. had not yet begun synthetic processes of this important material, and SOCMA was keen to ensure the U.S. did not become dependent upon a foreign source of supply. In 1927, synthetic methanol was determined to have rapidly replaced the imported product.

- 1925: Geneva Protocol prohibited the use of chemical and biological weapons in war. This was of interest to SOCMA membership, as many chemicals used in warfare are used to manufacture daily products in times of peace.

- 1926: Dr. Charles Herty retires as President of SOCMA, is named Honorary Member.

- 1927: SOCMA’s second President, Dr. August Merz, Calco Chemical Division of the American Cyanamid Company, succeeded Dr. Charles Herty and held the position through to 1945.

- 1927: SOCMA Board of Governors votes to begin a series on “Reports of Individual Companies,” where each member “should tell something of his company, its products, plans and aims.”

- 1927: Industry reports greatest consumption of vat dyes – a class of dyes that are classified as such because of the method by which they are applied.

- 1929: The textile industry, a key end-use market for synthetic organic chemicals, performed so poorly throughout the decade that any change into the 1930s would be considered positive.

- 1929: Further future industry outlook – SOCMA anticipated the coming decade as one of greater activity and satisfactory business performance. And “it would seem that the [economic] developments of the past year point to a satisfactory 1930, [especially considering] concerted efforts are under way to offset any bad effects that the recent stock market readjustment had on all industries.”

1930s

Despite the country’s economic conditions in the early part of the decade, SOCMA as an organization enjoyed the growing success of the specialty chemicals industry. SOCMA membership at times grew, or remained steady, with an average of 45 members at the end of each year. Annual meeting minutes reflect the association’s well-sustained ability to serve and address particular needs of individual member companies, as well as broader impacts to the industry.

Key Decade Events:

- 1930s: SOCMA asked members to be vigilant in educating the public through all available means and with an insistent attitude to demonstrate the essential and indispensable nature of the specialty chemicals industry to prevent foreign producers of similar products from taking control, as well as keep production costs low in the U.S.

- 1930s: There were a myriad of imports of coal-tar court cases involving:

- Question of mixtures

- Inflation and its impacts to the industry

- The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA)

- Prohibition of price fixing

- Strict limitation to purely interstate commerce

SOCMA stayed attuned to the activities growing out of Germany and its financial policies, including the German Reich’s “Reichsmark” being rendered “meaningless” due to varying comparisons between dollar and Reichsmark.

- Mid-late 30s – The chemical aspects of the reciprocal trade agreements, which were unclear in the early decade, began to take shape.

- 1934: December 6, 1934, Annual Meeting (held at the Chemists’ Club, NYC) – SOCMA recognized the contributions made to the industry to the following with bronze plaques:

- Dr. Charles H. Herty – SOCMA first President

- Hon. Francis P. Garvan – President, Chemical Foundation, Inc. in 1934 – formerly the Alien Property Custodian when the United States declared war on Germany, overseeing the seizure of ownership of chemical patents owned by Germany at the time of war declaration.

- Mr. Morris R. Poucher – Co-founder of SOCMA, pioneer of dyestuff industry in America

- 1936 Minutes of Annual Meeting: “…the advantages enjoyed by relatively small groups like ours in their ability to meet and conduct similar affairs in executive sessions, where the good stuff is all off the record, something impossible at large organizations where such matters must be conducted in select committees. You simply have to come out to get the good stuff first-hand.”

- U.S. v. General Dyestuff Corp. on Discharge Blue BG Extra: SOCMA considered this case “of most vital importance to the industry” – as its verdict was in favor of the importer (prior to appeals). If the importer succeeds in having a principle established that the importer could change by a slight percentage each importation, thus making it impossible for the domestic interest to keep up with the importer.

- 1930: Williamson Bill – Legislation providing for the transfer of industrial alcohol control from the Department of Treasury to the Department of Justice. SOCMA endorsed the side of industry consumers, who preferred industrial alcohol control to remain in the hands of the Treasury.

- 1931: SOCMA’s Statistics and Patents Service – Annual survey of import statistics that became increasingly valuable – used more than ever by membership in 1931.

- 1933: NRA (National Recovery Act) and the New Deal – SOCMA felt the impact of this Act on industry was “a nuisance.”

- 1934: Reciprocal Tariff Act – SOCMA concerned on Act’s probable effects to the industry.

- 1935: Reciprocal Trade Agreement with Belgium, effective May 1 – SOCMA interested to see what will develop in the way of increased imports and exports under agreement.

- Mid 1930s: There were six trade treaties in effect – Sweden, Belgium, Haiti, Cuba, Canada, Brazil. SOCMA was not ready to judge the results/success of such treaties yet.

- Late 1930s: A renewed interest in certain aspects of trade practices of the specialty chemicals industry came about. These interests and concerns were referred to SOCMA’s Trade Practice Committee for review and future recommendations.

1940s

The 1940s saw American developments far outpacing the world in synthetic organic chemistries. With the growing success of its member companies and the importance of their products, SOCMA’s mission strengthened upon itself to safeguard their interests, endeavoring to seek solutions to problems its members faced and to maintain a close watch on their welfare. The association was by this time proficient in cooperating with various executive government departments and federal agencies in all matters relating to the industry.

The effects of World War II were disruptive to many industry projects aimed at the improvement of products and production of new products. Peacetime research was stifled due to the War, but by the mid-1940s such innovative research was resuming. It should be noted that Wartime research and such emphasis placed on productions for war purposes resulted in the development of many new materials that have important uses in times of peace. SOCMA and the specialty chemicals industry overall was proud of its war efforts and collaborations with war agencies.

Key Decade Events:

- By the early 1940s, the industry was no longer reliant solely upon coal-tar products for fundamental intermediates.

- By the early 1940s, SOCMA was in close cooperation with various agencies of government, including:

- Customs Bureau of the Department of Treasury

- Bureau of Census and Foreign & Domestic Commerce of the Department of Commerce

- U.S. Tariff Commission

- Department of Justice

- 1940: American imports increased by $400M, with biggest increases in silk, rubber, tin and other raw materials.

- By the early 1940s, the National Defense and Preparedness initiative was created due to explosions and fires at plants working on war-time and defense orders.

- Mid-1940s saw enormous advancements in petroleum and natural gas chemistry. Research into natural gas chemistry greatly enlarged the field of intermediates available for specific utilization of specialty chemical fields.

- 1946: SOCMA named its third President, Ralph E. Dorland of Dow Chemical Company.

- In the first year of his presidency, SOCMA membership increased substantially, from 61 to 76.

- 1946: SOCMA marked its 25th Anniversary at its December 1946 Annual Meeting.

- The association reflected on how far the United States had come in forming, growing and thriving within its own synthetic organic chemical industry

- WWI embargo on imports forced the U.S. to supply its own materials quickly, thus creating the incentive for many more manufacturers to enter the field.

- 1947: 15 original members still remained within the SOCMA membership, and 22 of the current members were part of original member companies that had been acquired and/or consolidated.

- 1949: General Thomas B. Wilson, Chairman of Board of U.S. Plastic Products, addressed the SOCMA annual meeting on Dec. 7, 1949. He focused on the specialty chemical industry’s and SOCMA member companies’ contributions to the advancements of:

- Transportation (cars, rail, aviation) – chemical applications to metallurgy, fuel consumption, lubrication and protective coatings.

- Agriculture – expanding fertility of soil and insecticides.

- Timber industry – ability to manufacture paper, laminated woods and veneers.

- Development of Cortisone in 1949.

- Late 1940s – SOCMA members endeavored in “creative chemistry,” with production of new finishes, new fabrics, new finishes for woods, metals and similar surfaces, plastics, rayons, nylons and textile fields.

1930s-50s: It should be noted that SOCMA worked very closely with the Manufacturing Chemists’ Association (MCA) – now the American Chemistry Council – and they shared many of the same member companies. In the annual meeting minutes of the late 30s/early 40s, discussion was had around whether SOCMA and MCA would become one association.

1950s

Thirty years into SOCMA’s establishment, the 1950s brought key changes to the organization. During the span of the decade, several committees were established or refocused to help the industry succeed. These committees would assist in the coming decades as restrictions slowly began to tighten. Throughout these years, SOCMA worked to standardize organic chemical names, change committee procedures and expand chemical understanding through education.

Key Decade Events:

- 1950: Customs Simplification Act of 1951 – a discussion took place on the American Selling Price of the provision of the Tariff Act and its general effect on SOCMA. Proposed provisions include abolishing the American Selling Price as a basis of customs duties.

- 1952: When the bill was approved in 1951, it was considered satisfactory by the International Relations Committee. No action will be taken unless there is an attempt to reinsert a section or amendment which would nullify the American Selling Price basis of evaluation.

- 1951: Torquay Conference resulted in severe tariff reductions. These reductions would be studied and a report prepared, analyzing the effects on the industry.

- 1952: SOCMA established a Customs Committee that included the following functions:

- Maintaining a working liaison with customs authorities to ensure examiners had up to date information that allowed them to determine more accurately the competitive and noncompetitive status of imports whose ad valorem duties are based on American Selling Price.

- 1952: SOCMA Board of Governors initiated an industrywide standardization of organic chemical names. This request was referred to the Customs Committee and to the Committee on Liaison with the Manufacturing Chemists’ Association as a project in which both associations were interested.

- 1954: Committee on Chemical Additives established.

- 1954: 98 manufacturers of synthetic organic chemicals were represented within SOCMA.

- 1954: Public Relations Subcommittee was asked to study problems pertaining to public relations and make recommendations to a long-range program designed to further objectives.

- 1955: International Commercial Relations committee appointed four groups, each charged with a particular area of committee activity:

- Trade Agreements

- Customs Simplification

- General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

- Foreign Investment Programs

- 1955: Technical Advisory Subcommittee was established on an as-needed basis. This group was expected to be thoroughly familiar with the Tariff Act, as well as qualified to aid the Customs Committee on whatever technical problems may arise with respect to administration of the Tariff Act.

- 1956: SOCMA material was placed for study in 1,058 science, vocational guidance, international affairs, and economic classes of high schools and colleges. This brings the number of classes to more than 7,000 that are learning the essentiality of the chemical industry.

- 1956: Mechanical Technical Committee was established to unify and formalize the Association’s control of its standards activities and to ensure that the standards program reflects the Association’s policy.

- 1957: A proposed bill would provide for the manufacture of butadiene from alcohol that will be made from surplus grain. It would help with the disposal of surplus agricultural products. SOCMA decided to oppose the bill. Such a subsidy was deemed as wrong and could lead to consequences in the industry.

- 1958: Food additives bill passed. It was expected that a cosmetic additives bill would follow in the next year. SOCMA then prepared its position similar to past positions, which included legal responsibility for testing on the formulator of the final product.

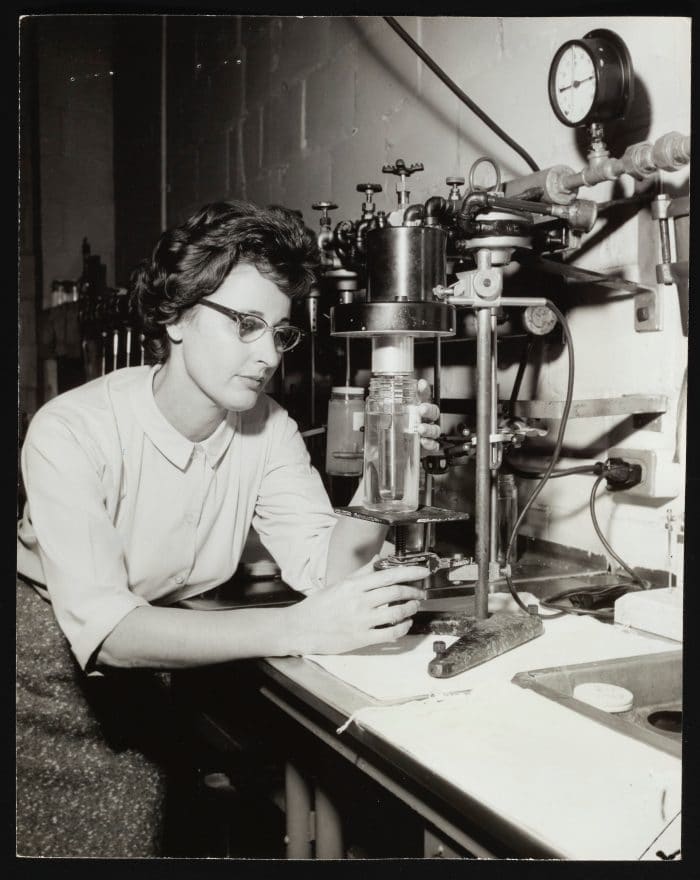

1960s

In the 1960s there was a shift in chemical legislation. The ripples created in the 60s transformed into waves in the following decades. A main focus of the decade was trade, especially in regard to the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 and the American Selling Price. SOCMA was at the fore- front, pushing for industry concerns through testimony, official statements and the creation of educational materi- als. Public relations for the Association also became a top of the mind initiative, especially near benzenoid plants.

Key Decade Events:

- 1960: International Commercial Relations Committee predicted that within the next few years, China would become a major source of chemicals in world trade. There was an attempt to gather data with respect to Chinese developments, citing that China could pose a tremendous threat to the world position of the U.S. in economic matters.

- 1960: SOCMA prepared a glossary of systematic and non-systematic names of synthetic organic chemicals in cooperation with the American Chemical Society.

- 1960: The Dyes Subcommittee worked towards FDA approval for the continued use of dyes in paper for food packaging.

- Regulation was finally passed in 1967, and SOCMA’s Food Additive Petition No. 367 was accepted for filing in 1963. SOCMA found the FDA’s recommendations to be satisfactory to protect public welfare and to permit the use of dyes in food packaging.

- 1961: SOCMA reorganized its Public Relations function and revised association literature.

- 1961: SOCMA continued to assume responsibility for cooperation with the American Chemical Society (ACS) in connection with the ACS Award for Creative Work in Synthetic Organic Chemistry.

- 1962: SOCMA advocated five important safeguards that Congress should include in the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (H.R. 11970). With the assumption the bill would pass, SOCMA made plans to produce an educational booklet illustrating the problems faced by the industry.

- Once passed, the International Commercial Relations Committee focused on:

- Customs, Common Market-free Trade Areas

- Anti-Dumping

- Organization of a new Foreign Trade Advisory Subcommittee

- Revision of Tariff Act Scheduled Subcommittee was discontinued because it had accomplished the purpose.

- Once passed, the International Commercial Relations Committee focused on:

- 1963: SOCMA supported the Anti-Dumping Act of 1921, which proposed a time limit of six months for the Treasury Department to determine whether the merchandise in question was being sold in the U.S., or elsewhere, at less than its fair value. This was viewed as helpful to both parties, as long as there was no burden placed on the Treasury Department in conducting a thorough investigation of the incident.

- 1964: SOCMA opposed an amendment to the Anti-Dumping Act with respect to proposed changes to confidentiality, advocating that existing confidentiality regulation should stand.

- 1964: To assist the Economic Studies Subcommittee in determining the most important chemical exports, SOCMA members were asked to anonymously submit a list of the 10 most significant exports to their businesses.

- 1964: The results of 10 task forces studying the effect of the Trade Expansion Act in 1962 on the various industry segments were extremely valuable. In the field of dyes, intermediates, plastics, plasticizers and resins, medicinal, flavors and perfumes, and rubber processing chemicals, arguments were developed from statistical studies for the retention of protection. Results were used in presentations to the Tariff Commission and the Trade Information Committee.

- 1965: After about 6 years of work, “SOCMA’s Handbook of Commercial Organic Chemical Names” was published.

- 1965: The Public Relations Committee held monthly press briefings with reporters from business and trade media to provide the association an opportunity to present new information in support of its positions.

- 1966: A Community Action Committee was formed to encourage member discussion of implications of government actions on company operations with community leaders and organizations.

- 1966: Union Relations Committee formed for the purpose of developing and encouraging contacts with labor unions to point out the implications of the GATT negotiations.

- 1968: Members of the Customs Subcommittee met on several occasions with customs officials to resolve questions regarding the administration of the American Selling Price (ASP) system. The subcommittee also provided several technical experts to serve as government witnesses in the Customs Court Cases.

- 1968: Trade Study Subcommittee became heavily involved in an analysis of the effect of Germany’s increased border taxes and export rebates on U.S. trade.

- 1968: Labor Relations Committee concerned itself with creating awareness among union leaders of labor’s stake in obtaining reciprocity in international trade. Concerns over the loss of the American Selling Price System. “It would imperil our domestic benzenoid industry and the jobs of our workers in this industry.”

- 1969: SOCMA monitored articles on the American Selling Price and developed a “letters to the editor” program because some of the reporters writing the articles did not have an understanding of the issue.

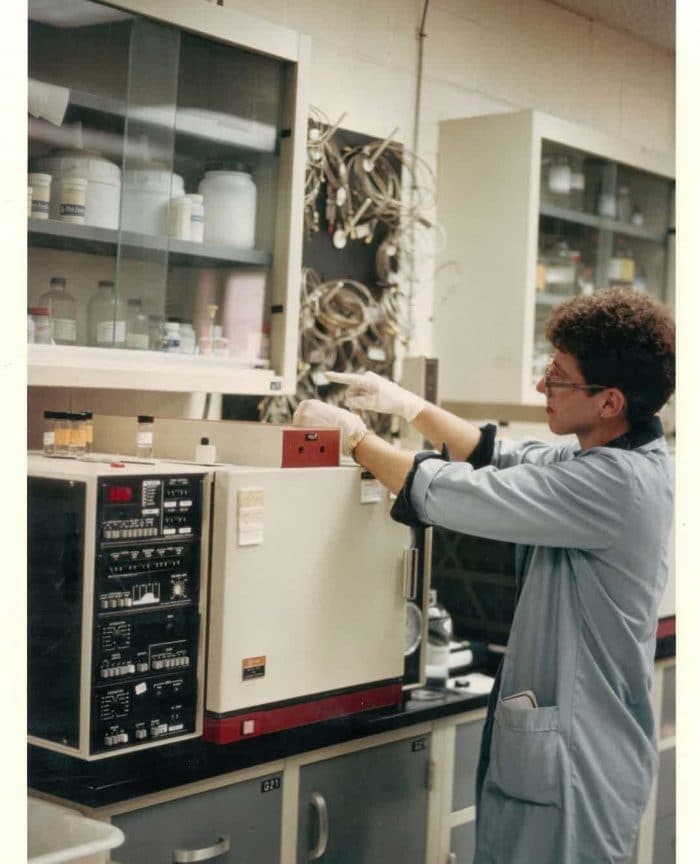

1970s

The 1970s ushered in an era of change and unknowns for SOCMA and the specialty chemical industry. Many agencies and regulations were created, including the Envi- ronmental Protection Agency (EPA), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). SOCMA helped the industry, and itsmembers navigate this unfamiliar landscape. Even though SOCMA did not always know the best course of action at the time, the organization collected research and informa- tion to stay on top of current issues. SOCMA supported the industry by creating new committees, surveying itsmembers, and offering relevant seminars.

.

Key/Interesting Decade Events:

- 1970: SOCMA relocated from New York to Washington, DC.

- 1970: Environmental Protection Agency established (EPA).

- 1971: Occupational Safety and Health Administration established (OSHA).

- 1972: Due to the organization of OSHA, companies were required to comply with numerous detailed regulations covering the health and safety of employees in their working environments. SOCMA developed a manual to provide a convenient do-it-yourself guide to OSHA regulations and requirements.

- 1974: Safe Drinking Water Act – SOCMA became interested in drinking water legislation because of its potential effect on upstream discharge of various pollutants.

- Final EPA guidelines for the state water discharge permit program included two SOCMA recommendations covering confidentiality of information and the designation of the person who signs the forms. In 1976, SOCMA found that the EPA fluctuated back and forth, and would continue to monitor closely.

- 1974: As a consequence of the Watergate scandal in 1972, SOCMA was unsure of what would happen with outstanding legislation. There was a pause on some of the issues from earlier in the decade and an overall state of confusion. SOCMA was particularly concerned that a Senate trial of the President later in the year would halt all legislative action.

- 1975: Dye Additives Committee was dissolved. With advances in food packaging technology, it was believed that SOCMA’s Food Additive Petition 367 was no longer viable and therefore withdrawn.

- 1975: SOCMA reorganized its Environment Committee into three areas of responsibility:

- EPA regulations

- OSHA regulations

- The Policy-level Committee was charged with reviewing overall association environmental policy.

- 1975: With respect to environmental matters, the Board was particularly interested in having the association consider long-term problems facing the industry in the coming years.

- 1976: Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) was passed by Congress with the Environmental Protection Agency implementing the new chemical control law.

- SOCMA held a workshop to provide significantly needed information to both large and small member companies. SOCMA also created a memorandum calling attention to TSCA concerns.

- 1976: Due to involvement with environmental activities, SOCMA added a part-time employee to handle such issues.

- 1977: SOCMA offered a seminar to help with restrictions on solid waste regulations and informal workshops to deal with broad EPA regulations.

- 1977: SOCMA launched its Association Management Services Group to manage consortia formed to address specific chemical or process advocacy, regulatory, testing, stewardship, or technical issues which were of interest to a particular sector of the chemical industry.

- 1979: SOCMA worked to understand the economic impact on a company that may not have a research staff to conduct tests, as these companies began hiring outside test labs and auditors to review the quality of data developed in in-house labs.

1980s

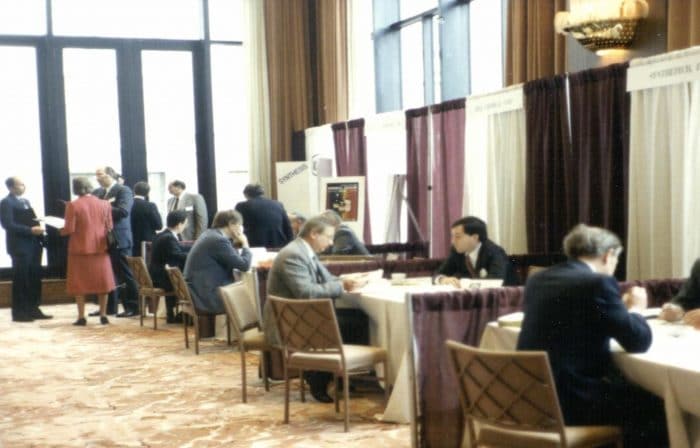

After several years of regulations on the chemical industry, the 1980s was a period of continued industry evolution. SOCMA was at the forefront of these protocols, pushing for member interests, especially for smaller specialty chemi- cal companies. SOCMA reorganized its structure to better accommodate the industry’s needs. During the decade, SOCMA continued to evaluate its benefit to the industry and proved to be a leading force. In 1985 SOCMA held the first InformEx Trade Show, a show that became the premier event for the industry until 2005.

Key Decade Events:

- 1980: SOCMA proposed a new administrative structure to adequately handle the growing number of projects and association activities. SOCMA’s work was divided into two broad areas – membership services and government relations, with a staff leader heading each of these areas of activity.

- 1980: Members urged SOCMA to undertake a study on the feasibility of developing a product liability program focused on the sudden and accidental release of materials causing injury.

- 1980: A Federalism Task Force was created. Objectives of the task force included:

- Studying federalism as it was promoted by the Reagan Administration.

- Making recommendations to the SOCMA Board regarding issues that affect the chemical industry.

- 1983: Amendments were made to the Safe Drinking Water Act and restrictions were placed on disposal of hazardous waste. SOCMA explored how industry could respond to proposals to prohibit land disposal of hazardous waste. Association goals included:

- Providing management assistance to members through a series of mini workshops

- Comment on EPA’s regulatory proposals

- Developing a program to address groundwater monitoring and EPA’s emerging policy

- Monitor the reauthorization of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA)

- 1984: OSHA hazard communication regulations led SOCMA to create goals for moving forward, including:

- Communicating analysis to membership and voicing concerns to OSHA

- A member survey to solicit information regarding problems encountered in interpreting the standard. This would help SOCMA to develop a position paper.

- 1985: First InformEx Trade show was held in Atlanta as a small event where each company was given a 6-foot table, two chairs and a company sign.

- 1986: SOCMA discussed whether or not InformEx should be an annual, semi-annual or even less frequent event. Due to the level of interest, InformEx 1987 was held with a maximum of 100 exhibitors. Ground rules to exhibit included no displays allowed other than minimal backdrops.

- 1986: SOCMA discussed membership structure, citing that $1,000 may be a burden for some of the smaller companies, creating disparity between smaller and larger companies. The Board also considered creating a member category for companies without direct U.S. operations.

- 1986: There was a push to disperse more information through a database system, using less paper.

- 1987: SOCMA worked to convince the EPA to develop RCRA regulations to preserve and increase flexibility of waste management practices for onsite storage of hazardous waste.

- 1988: SOCMA’s first Commercial Guide was published, and in 1990, SOCMA looked to produce an expanded version of the guide in a magazine format that would be compiled and printed by Performance Chemicals Magazine.

1990s

The 1990s began with continued efforts to communicate the industry’s concerns to the EPA. SOCMA incorporated Responsible Care into its membership requirements. The program held chemical companies to a baseline standard, requiring manufacturers to improve their performance in environmental protection, occupational safety and health protection, plant safety, product stewardship and logistics. As technology began to advance, SOCMA adapted with it. In 1996, SOCMA launched its first website.

Key Decade Events:

- 1990: Continued efforts to communicate the association’s concerns to EPA as the agency implements concepts under the Toxic Substances Control Act.

- 1991: SOCMA implemented Responsible Care for all manufacturing members.

- 1992: An Audit Committee was created, consisting of three to five members. It would be led by a non-officer governor and required at least one member with financial skills as well as one staff member.

- 1993: SOCMA reviewed options for non-dues revenue sources, including the publication of the Commercial Guide in conjunction with Performance Chemicals.

- 1993: The Responsible Care Task Force became a standing Committee of SOCMA and was renamed the Responsible Care Committee.

- 1994: A Public Affairs Group was created consisting of staff from Government Relations, Responsible Care, Communications and Training.

- 1994: Progress was made on a new SOCMA Government Relations Advocacy Database. This was an effort to identify all SOCMA member facilities by the congressional districts in which they reside and enabled SOCMA to improve the strength of its advocacy program.

- 1996: SOCMA launched its first website.

- 1996: SOCMA commemorated its 75th Anniversary, under the leadership of President Graydon R. Powers and Chairman Wayne Tamarelli, CEO, Dock Resins Corporation. At 75 years, SOCMA saw itself as a fast-moving, rapidly growing trade association.

- 1997: SOCMA changed its dues structure, creating a system of dues categories based on member sales volume rather than the existing individual company calculation based on sales.

- 1997: To achieve operating cost reductions, SOCMA moved its offices to 1850 M Street in Washington, DC, from 1330 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Washington, DC.

- 1997: SOCMA remained aware of the agenda of environmental activists and responded to the need for SOCMA to play an integral role in helping members convey to their local communities a positive message regarding the importance of chemicals in daily life.

- 1998: The InformEx Committee developed a 5-year plan addressing key issues such as bringing clearer focus on the purpose of InformEx, the role of educational seminars at InformEx and a mechanism to ensure a succession of dedicated members for the InformEx Committee.

- 1998: Discussion took place on EPA’s landmark High Production Volume (HPV) testing initiative, with the Board approving an HPV position paper that became part of the Board’s Policies and Procedures Manual.

- 1999: SOCMA circulated a member survey to gauge the membership’s preparation for Y2K, which indicated they were suitably prepared by October, well before year’s end.

- 1999: International member companies were required to practice Responsible Care or “like kind” programs. Bylaws were amended in 2000 to reflect this mandate.

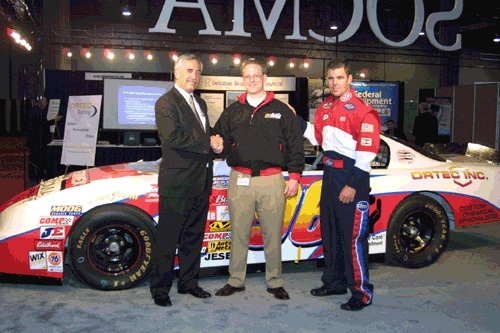

2000s

In 2000, SOCMA entered a decade with many internal changes. 2005 was an especially significant year with the sale of InformEx and the adoption of ChemStewards®. Due to the trade show sale, SOCMA had to reconsider revenue sources and determine its future as an organization, which led to a name change. In 2009, the Synthetic Organic Chemical Manufacturers Association officially changed its name to the Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Affiliates.

Key Decade Events:

- 2001: SOCMA’s legislative and regulatory challenges included working with the US. Chemical Safety & Hazard Investigation Board on its Hazard Investigation Study of Reactive Chemicals. SOCMA members were asked to participate in a select number of surveys and plant site visits.

- 2001: OSHA issued a new Recordkeeping Standard, and SOCMA held a compliance workshop in cooperation with other associations. SOCMA employed tools to assist members in achieving Practice-in-Place on Process Safety.

- 2003: InformEx looked to become the world’s premier custom chemical service exhibition, remaining focused on meeting the commercial networking needs of SOCMA member companies and becoming a significant and positive contributor to the Association’s financial health.

- 2003: An InformEx web portal was successfully created, allowing attendees to interact with each other.

- 2004: A 20-year celebration of InformEx was held in Las Vegas. About 450 exhibitors, including 206 SOCMA members, set up booths in almost 250,000 square feet of space at the Sands Expo Center.

- 2005: InformEx was sold to UBM, and the association reconsidered its revenue sources post-InformEx.

- 2005: SOCMA replaces Responsible Care with ChemStewards®, as the association’s flagship environmental, health and safety program.

- 2006: Government Relations goals for the year included increasing international advocacy; expanding agency outreach and promoting ChemStewards®; creating a grassroots advocacy program; and promoting GR successes.

- 2007: The Performance Improvement Committee worked on branding ChemStewards® and planned to revamp the awards program to tie in educational outreach.

- 2008: The EPA issued a list of 15 substances for which there was a requirement to capture no less than 90% of the source emissions. EPA proposed its National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAPs) for chemical manufacturing area sources. The proposed rule applied to chemical manufacturing operations at any of these nine chemical manufacturing area source categories that process, use, produce or generate any of 15 listed urban HAPs.

- 2009: The association’s name was officially changed to the Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Affiliates to represent the value chain more broadly, and a new logo accompanied the change.

- 2009: The Operator Training Manual was completed and was distributed electronically.

2010s

In recent years, SOCMA has rebranded, reentered the trade show space and continued to be a leading industry force. SOCMA supports its members and the industry with the latest knowledge, an unparalleled peer network and highly customized resources. Towards the end of the decade, SOCMA released an updated Chemical Operator Training program that includes animations of process equipment that assist operators in more easily retaining the information.

Key Decade Events:

- 2010: SOCMA Board adjusted the dues structure to reflect North American sales.

- 2011: Financial funding was provided for:

- SOCMA branding campaign

- Expanded and modernized ChemStewards®

- Regional Government Relations meetings

- 2012: SOCMA was focused on these key regulations:

- EPA’s Chemical Manufacturing Area Sources (CMAS) Rule and its proposal to require public disclosure of chemical identity under the Toxic Substances Control Act.

- A final rule on the Globally Harmonized System, released by the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, that made changes to Hazard Communication Standards.

- 2013: SOCMA began to optimize the ChemStewards program by creating a cloud-based web interface for participants.

- 2016: Jennifer Abril became SOCMA’s first female President & CEO – Jennifer had previously worked at SOCMA and led the development of the ChemStewards® program.

- 2017: SOCMA moved its offices to the Crystal City neighborhood of Arlington, VA, just across the river from Washington, DC.

- 2017: SOCMA launched a modernization effort for its longtime Chemical Operator Training Program, resulting in a digital tool that includes animations, additional curriculum and other features that enhance learning and plant safety.

- 2019: SOCMA launched a refreshed brand and adopted a new tagline, “Solutions for Specialties.”

- 2020: SOCMA reentered the trade show business with the acquisition of the Specialty & Custom Chemicals Show from Chemicals America. The show has been located in Fort Worth, Texas for its first 3 years.

Categorized in: Uncategorized